Over the weekend, I have been taking a deeper look into a piece that I wrote a while back that I like to call “Renaissance Jam” or “Renaissance Orchestra”. As the name implies, it sounds like something that could have been written in the 16th century. It is also a fun and hypnotic progression that I always thought would make it fitting for players to improvise (hence the word “jam”).

Peculiar Progression

I don’t know how in the world I imagined such a piece because there are aspects of the progression that remain mysterious to me to this very day. The basic outline of the chord progression is as follows: A minor, G major, Bb major, and D major. At the end (at D major), there is a turnaround of F major and G major, which can bring us back to the beginning (A minor), A major, or can take us to D major.

Renaissance music is known for having some peculiar chord progressions. Mainly guided by voice leading (i.e. the melodic direction of the individual pitches), music from the renaissance did not always fit into the nice “boxes” that chord progressions typically have since the 1600’s. In other words, by focusing on the individual (and most often singable) melodies, crafting beautiful lines first, and only then finding places for all the voices to converge “as chords”, musicians of the renaissance created unique progressions that are unimaginable if one takes a “chord first” approach.

The reason why the chord progression in my piece is peculiar is because there are no keys to which A minor, G major, Bb major, and D major are all native. In fact, G major and Bb major both have two different kinds of B pitches–the former a natural and the latter a flat. These two chords, being only a measure apart, “should” result in a terrible sound. However, what keeps it sounding good is how the notes are approached and introduced (i.e. voice leading).

Examination of Voice Leading

So how did I get away with such a peculiar progression? Let’s examine the voice leading, but first let’s see what we can learn from some examples of pieces from the renaissance.

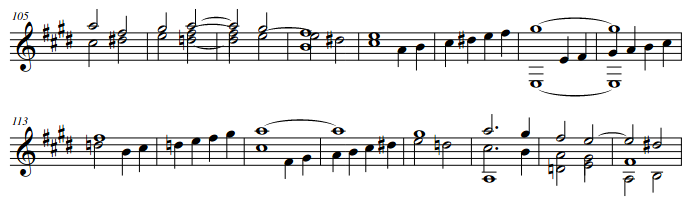

The following example is Ricercare #3 by Francesco DaMilano, also known as “Il Divino” or “The Devine” for his amazing command of the lute. In the following example, the voices alternate between D sharp and D natural. Although the motion can sound unfamiliar to the modern ear, none of the voice leading sounds like it has “violated the rules”. In other words, nothing about this section sounds bad. The D natural pitches tend to bring us to the C# in an A major chord, and the D sharp pitches tend to bring is to the E in an E major chord. There are two times that the D natural brings us up to the E in an E major chord (mm. 106 and 119), but the motion does not sound contrived.

Try the following example for yourself. It is taken from measures 116-119 above.

As for my piece, it has its own peculiar cross relation. Other than the B to Bb motion described above, the following occurs in the F –> G –> D turnaround.

You can even have a little fun with it with added embellishments as well. Try the following

A “Renaissance Jam” Version of Giant Steps?

One way that I often describe this piece is like a Renaissance version of John Coltrane’s Giant Steps. Similar to Giant Steps, Renaissance Jam is meant to be a jam piece, an improvisational work for performers. Also similar to Giant Steps, and mentioned earlier, the chord progression is unusual. In John Coltrane’s work, there are unique turns that take one chord into the next. The name “Giant Steps” is said to come from the minor third movements from one group of chords to the next. (Note: a minor third is one half step higher than a major second, hence a “giant” step”). In my work, a similar “stretch” brings one chord to the next (e.g. G major –> Bb Major, the latter a minor third higher than the former).

“[T]he bass line is kind of a loping one. It goes from minor thirds to fourths, kind of a lop-sided pattern in contrast to moving strictly in fourths or in half-steps.”

John Coltrane, quoted from Album Liner Notes

Next Steps for Renaissance Jam

I plan to create a “concert version” (i.e. highly embellished, virtuosic version) of this piece. 20th century composer, Joaquín Rodrigo, wrote many new and original works based on older pieces from the 16th and 17th centuries. In this vein, I plan to take the “jam” piece I wrote, and create a new concert version. Watch the video below for a sneak peak of the latest developments.

Interested in studying the original version? It is available in the shop. Special thanks to all my members/patrons for making posts like this possible, and supporting my future work.

Comments (2)

I just added two videos to https://www.devinulibarri.com/product/renaissance-by-devin-ulibarri/ The first video gives some background, and the second video is the live performance of this piece as performed at Hummingbird Music Camp. Check it out to hear the original with an awesome solo by Jazz musician, Phil Arnold.

Update: My latest draft can be previewed at https://media.publit.io/file/2021-02-15-133523.html